In many contexts, all of the individual members of a group canbenefit from the efforts of each member and all can benefitsubstantially from collective action. For example, if each of uspollutes less by paying a bit extra for our cars, we all benefit fromthe reduction of harmful gases in the air we breathe and even in thereduced harm to the ozone layer that protects us against exposure tocarcinogenic ultraviolet radiation (although those with fair skinbenefit far more from the latter than do those with dark skin). If allof us or some subgroup of us prefer the state of affairs in which weeach pay this bit over the state of affairs in which we do not, thenthe provision of cleaner air is a collective good for us. (If it costsmore than it is worth to us, then its provision is not a collectivegood for us.)

- Free Ride, a 1978 album by Marshall Hain; Free Ride, a 2004 album by Carson Cole; Songs 'Free Ride' (song), a 1975 song by Dan Hartman for the Edgar Winter Group 'Free Ride', a song by Nick Drake on the album Pink Moon 'Free Ride', a song by Annabelle Chvostek on the album Bija 'Free Ride', a song by the Concretes on the album Nationalgeographic.

- Luggie is the only folding scooter with folding variation to support leveage the scooter and storage the scooter in any constrained space.

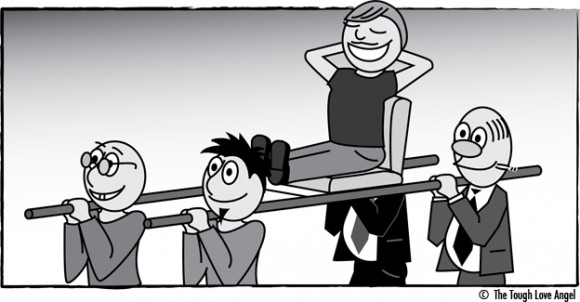

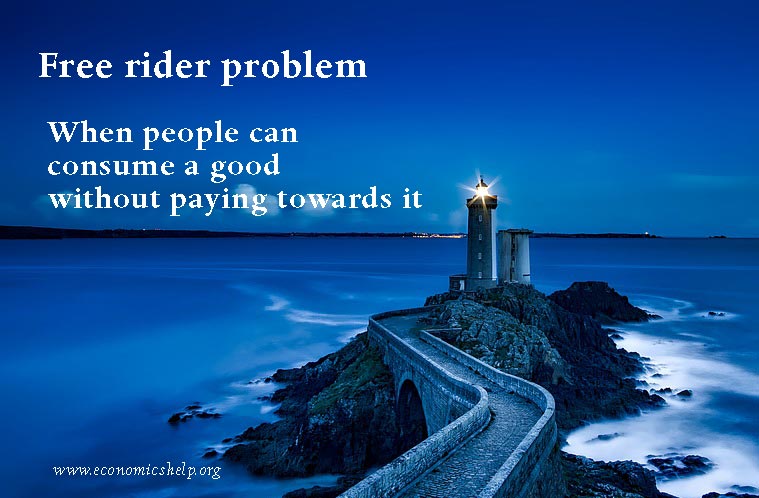

- The free rider problem refers to a case where a few individuals tend to utilize beyond their fair share or pay less than the standard cost of a shared product or service. This situation is treated as market failure that takes place when people exploit the scenario of utilizing a common resource without having to pay for it.

Unfortunately, my polluting less does not matter enough for anyone—especially me—to notice. Therefore, I may not contribute my share toward not fouling the atmosphere. I may be a freerider (or free rider) on the beneficial actions ofothers. A free rider, most broadly speaking, is someone who receives a benefit without contributing towards the cost of its production. The free rider problem is that the efficient production of important collective goods by free agents is jeopardized by the incentive each agent has not to pay for it: if the supply of the good is inadequate, one’s own action of paying will not make it adequate; if the supply is adequate, one can receive it without paying. This is a compelling application of the logic of collective action, an application of such grave import that we pass laws to regulate the behavior of individuals to force themto pollute less.

Free Rider HD is a game where you race bikes on tracks drawn by other players. Thousands of top tracks to race or draw your own! Download free games at FreeRide Games. All PC game downloads are free to download. The PC games are 100% safe to download and play.

The free rider problem gives rise to large explanatory and normative questions in six main disciplines. Social psychology asks: To what extent and in what circumstances are people motivated to free ride? and What sorts of negative incentives are effective in motivating cooperation when free riding is possible? Game theory asks: Under what strategic circumstances does the rational promotion of individual self-interest recommend free riding? Informed by those two areas of enquiry, mainstream economics then asks: What real-world mechanisms are the most efficient ways of producing public goods, given the incentives to free ride? Political science asks: What explains the existence of large-scale political participation, despite the incentives that favor free riding? Moral philosophy asks: Under exactly which circumstances is free riding morally wrong? and What explains why it is wrong (when it is)? And relatedly, normative political philosophy asks: Do the moral reasons against free riding supply a satisfactory grounding for political obligation?

- 1. The Logic of Collective Action

1. The Logic of Collective Action

The strategic structure of the logic of collective action is that ofthe n-prisoner’s dilemma (Hardin 1971, 1982a). If nis 2 and the two members are able to coordinate on whether they acttogether, there can be no free rider unless one of the members is defacto altruistic. As represented in Game 1, prisoner’s dilemma for twoplayers is essentially the model of exchange (Hardin 1982b). Supposethat, in the status quo, I have a car and you have $5000 but that bothof us would prefer to have what the other has. Of course, each of uswould rather have the holdings of both of us: both the money and thecar. The second best outcome for both of us would be for you to have mycar in exchange for my having your money. The status quo is a worsestate of affairs for both of us than that in which we succeed inexchanging. In the matrix, the outcomes are ordinally ranked from best(1) to worst (4) for each player. For example, the outcome (upper rightcell) in which you yield the money and I keep the car is worst (4) foryou as the Row player and best (1) for me as the Column player.

| Column | |||

| Yield car | Keep car | ||

| Row | Yield $5000 | 2, 2 | 4, 1 |

| Keep $5000 | 1, 4 | 3, 3 | |

Game 1: Prisoner’s Dilemma or Exchange

As an n-prisoner’s dilemma for n ≫ 2,collective action is therefore essentially large-number exchange. Eachof us exchanges a bit of effort or resources in return for benefitingfrom some collective provision. The signal difference is that I cancheat in the large-number exchange by free riding on the contributionsof others, whereas such cheating in the two-person case would commonlybe illegal, because it would require my taking from you without givingyou something you prefer in return.

In some collective provisions, each contribution makes the overallprovision larger; in some, there is a tipping point at which one or afew more contributions secure the provision—as is true, for example,in elections, in which a difference of two more votes out of a verylarge number can change defeat into victory. Even in the latter case,however, the expected value of each voter’s contribution is the same exante; there is no particular voter whose vote tips the outcome. Let us,however, neglect the tipping cases and consider only those cases inwhich provision is, if not an exactly linear function of the number ofindividual contributions or of the amount of resources contributed, atleast a generally increasing function and not a tipping or stepfunction at any point. In such cases, if n is very large and you do notcontribute to our collective effort, the rest of us might still benefitfrom providing our collective good, so that you benefit withoutcontributing. You are then a free rider on the efforts of the rest ofus.

Unfortunately, each and every one of us might have a positiveincentive to try to free ride on the efforts of others. Mycontribution—say, an hour’s work or a hundreddollars—might add substantially to the overall provision. But mypersonal share of the increase from my own contribution alone might bevanishingly small. In any case of interest, it is true that my benefitfrom having all of us, including myself, contribute is far greaterthan the status quo benefit of having no one contribute. Still, mybenefit from my own contribution may be negligible. Therefore I andpossibly every one of us have incentive not to contribute and to freeride on the contributions of others. If we all attempt to free ride,however, there is no provision and no ‘ride.’

The scope for free riding can be enormous. Suppose our large groupwould benefit from providing ourselves some good at cost to each of us.It is likely to be true that some subgroup, perhaps much smaller thanthe whole group, would already benefit if even only its own memberscontribute toward the larger group’s good. Suppose this is true for k≪ n. This k-subgroup now faces its own collective actionproblem, one that is perhaps complicated by the sense that the largenumber of free riders are getting away with something unfairly. If oneperson in an exchange tried to free ride, the other person would mostlikely refuse to go along and the attempted free ride would fail. But ifn − k members of our group attempt to free ride,the rest of us cannot punish the free riders by refusing to go alongwithout harming our own interests.

1.1 History

The free rider problem and the logic of collective action have beenrecognized in specific contexts for millennia. Arguably, Glaucon inPlato’s Republic (bk. 2, 360b–c) sees the logic in hisargument against obedience to the law if only one can escape sanctionfor violations. First-time readers of Plato are often astonished thatdear old Socrates seems not to get the logic but insists that it is ourinterest to obey the law independently of the incentive of itssanctions.

Adam Smith’s argument for the invisible hand that keeps sellerscompetitive rather than in collusion is a fundamentally important andbenign—indeed, beneficial—instance of the logic of collectiveaction. He says that each producer “intends only his own gain,and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand topromote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always theworse for the society that it was no part of [the individual’s intendedend]. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that ofsociety more effectually than when he really intends to promoteit” (Smith [1776] 1976, bk. 4, chap. 2, p. 456). The back of theinvisible hand swats down efforts at price collusion, thereby pushingproducers to be innovative.

David Hume grasps the generality of the problem clearly. Hesays:

Two neighbours may agree to drain a meadow, which theypossess in common; because ‘tis easy for them to know each other’smind; and each must perceive, that the immediate consequence of hisfailing in his part, is, the abandoning the whole project. But ‘tisvery difficult, and indeed impossible, that a thousand persons shou’dagree in any such action; it being difficult for them to concert socomplicated a design, and still more difficult for them to execute it;while each seeks a pretext to free himself of the trouble and expence,and wou’d lay the whole burden on others. (Hume [1739–40] 1978, bk. 3,part 2, sect. 8, p. 538).

John Stuart Mill ([1848] 1965, book 5, chap. 11, sect. 12) expressesthe logic very clearly in his defense of laws to require maximum hoursof work. He supposes that all workers would be better off if theworkday were reduced from, say ten to nine hours a day for all, butthat every individual worker would be better off working the extra hourif most others do not. The only way for them to benefit from theshorter workday, therefore, would be to make it illegal to work longerthan nine hours a day.

Vilfredo Pareto stated the logic fully and for the general case:

If all individuals refrained from doing A, everyindividual as a member of the community would derive a certainadvantage. But now if all individuals less one continuerefraining from doing A, the community loss is very slight, whereas theone individual doing A makes a personal gain far greater than the lossthat he incurs as a member of the community. (Pareto 1935, vol. 3,sect. 1496, pp. 946–7)

Pareto’s argument is framed for the negative case, such as theexample of pollution above, but it fits positive provisions as well.Unfortunately, his argument is buried in a large four-volume magnumopus that is a rambling discussion of many and varied topics, and itseems to have had little or no influence on further discussion.

Finally, the logic of collective action has long been generalized ina loose way in the notion of the free rider problem. And it is capturedin the popular slogan, “Let George do it,” in which Georgetypically stands in for the rest of the world.

Despite such frequent and widespread recognition of the logic, itwas finally generalized analytically by Mancur Olson only in 1965 inhis Logic of Collective Action. The odd mismatch of individualincentives and what may loosely be called collective interests is theindependent discovery of two game theorists who invented the prisoner’sdilemma for two persons (see Hardin 1982a, 24–5) and of variousphilosophers and social theorists who have noted the logic ofcollective action in various contexts. In Olson’s account, what hadbeen a fairly minor issue for economists became a central issue forpolitical scientists and social theorists more generally. From early inthe twentieth century, a common view of collective action in pluralistgroup politics was that policy on any issue must be, roughly, a vectorsum of the forces of all of the groups interested in the issue (Bentley1908). In this standard vision, one could simply count the number ofthose interested in an issue, weight them by their intensity and thedirection they want policy to take, and sum the result geometrically tosay what the policy must be. Olson’s analysis abruptly ended this longtradition; and group theory in politics took on, as the central task,trying to understand why some groups organize and others do not.

Among the major casualties of Olson’s revision of our views of groupsis Karl Marx’s analysis of class conflict. Although many scholarsstill elaborate and defend Marx’s vision, others now reject it asfailing to recognize the contrary incentives that members of theworking class face. (Oddly, Marx himself arguably saw thecross-cutting—individual vs. group—incentives ofcapitalists, the other major group in his account.) This problem hadlong been recognized in the thesis of the embourgeoisement of theworking class: Once workers prosper enough to buy homes and to benefitin other ways from the current level of economic development, they mayhave so much to lose from revolutionary class action that they ceaseto be potential revolutionaries.

In essence, the theories that Olson’s argument demolished were allgrounded in a fallacy of composition. We commit this fallacy wheneverwe suppose the characteristics of a group or set are thecharacteristics of the members of the group or set or vice versa. Inthe theories that fail Olson’s test the fact that it would be in thecollective interest of some group to have a particular result, evencounting the costs of providing the result, is turned into theassumption that it would be in the interest of each individual in thegroup to bear the individual costs of contributing to the group’scollective provision. If the group has an interest in contributing toprovision of its good, then individual members are (sometimes wrongly)assumed to have an interest in contributing. Sometimes, this assumptionis merely shorthand for the recognition that all the members of a groupare of the same mind on some issue. For example, a group of anti-warmarchers are of one mind with respect to the issue that gets themmarching. There might be many who are along for the entertainment, tojoin a friend or spouse, or even to spy on the marchers, but the modalmotivation of the individuals in the group might well be the motivationsummarily attributed to the group. But very often the move fromindividual to group intentions or vice versa is wrong.

This fallacious move between individual and group motivations andinterests pervades and vitiates much of social theory since at leastAristotle’s opening sentence in the Politics. He says,

We see that every city-state is a community of some sort,and that every community is established for the sake of some good (foreveryone performs every action for the sake of what he takes to begood). (Aristotle Politics, book 1, chap. 1, p.1)

Even if we grant his parenthetical characterization of individualreasons for action, it does not follow that the collective creation ofa city-state is grounded in the same motivations, or in any collectivemotivation at all. Most likely, any actual city-state is the product inlarge part of unintended consequences.

Argument from the fallacy of composition seems to be very appealingeven though completely wrong. Systematically rejecting the fallacy ofcomposition in social theory, perhaps especially in normative theory,has required several centuries, and invocation of the fallacy is stillpervasive.

2. Public Goods

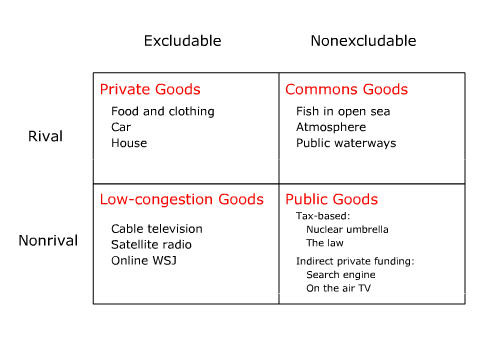

Olson based his analysis on Paul Samuelson’s theory of public goods.Samuelson (1954) noted that some goods, once they are made available toone person, can be consumed by others at no additional marginal cost;this condition is commonly called jointness of supply or nonrivalnessof consumption, because your consumption of the good does not affectmine, as your eating a lovely dinner would block my eating it.Therefore, in standard price theory, in which price tends to equate tomarginal cost, such goods should have a zero price. But if they arepriced at zero, they will generally not be provided. In essence, pricetheory commends free riding on the provision of such goods. This mightsound like merely a cute logical problem; but standard examples includeradio broadcasts, national defense, and clean air. If any of these isprovided for anyone, they are de facto provided for everyone in therelevant area or group.

There is a second feature of Samuelson’s public goods that wouldmake them problematic in practice: the impossibility of exclusion. Oncesupplied at all, it is supposedly impossible to exclude anyone from theconsumption of a public good. It is often noted that this feature isanalytically interesting but empirically often beside the point. Statesoften forcibly exclude people from enjoying such public goods as radiobroadcasts. Others can be provided through the use of various devicesthat enable providers to charge the beneficiaries and to exclude thosewho do not pay, as for example, by advertising that imposes a cost ontelevision viewers or the use of cable rather than broadcasting overthe air to provide television programming at a substantial price.Exclusion is merely a problem of technology, not of logic. With presenttechnology, however, it may be too expensive to exclude many people andwe may therefore want the state to provide many goods so that we canavoid the costs of exclusion.

There are some compelling cases of goods that are both joint insupply and nonexcludable. National defense that protects cities againstattack from abroad, for example, is for all practical purposes a goodwith both these features. But the full logic of public goods is oflittle practical interest for many important contexts. Indeed, what areoften practically and politically interesting are goods that are infact provided collectively, independently of whether they have eitherof the defining features of public goods. We can even provide purelyprivate consumptions through collective choice. For example, mostwelfare programs transfer ordinary private consumption goods orresources for obtaining these. Although technically these are notpublic goods in Samuelson’s sense, we can refer to them as collectivegoods and we can treat provision of them as essentially problems ofcollective action.

Olson notes that very many politically provided goods, such ashighways and public safety, roughly have the qualities of Samuelson’spublic goods and therefore face the problem of free riding thatundercuts supply of the goods. Note that the supply of such goods bythe state overcomes the free rider problem because voters can vote onwhether everyone is required to pay toward the provision, as in thecase of national defense. If I am voting whether the good is to beprovided, I cannot free ride and I need not worry that anyone else caneither. We can all vote our overall preferences between supply at therelevant individual cost versus no supply and no cost of provision, sothat democratic choice turns our problem into a simplecoordination—if we are all in agreement that a relevant goodshould be collectively provided.

From the analysis of the de facto logic of collective action thatwould block the spontaneous provision of many fundamentally importantclasses of collective goods we can go on to argue for what is now oftencalled the public-goods theory of the state (Baumol 1952, 90–93; moregenerally see Hardin 1997). The public-goods account gives us a clearnormative justification of the state in welfarist terms: The stateresolves many centrally important and potentially pervasive free riderproblems. It does not give us an explanatory account of the origins ofthe state, although it could arguably contribute to the explanation ofthe maintenance of a state once it exists. It might do so throughsupport for the state’s collective provisions and, therefore, supportfor the state. Unfortunately, as libertarians are quick to note, givingthe state power to resolve certain free rider problems also gives it thepower to do many other things that could not be justified with similarnormative arguments.

3. Self-Interest Theory

The modern view of the fallacy of composition in social choice is aproduct of the understanding of politics as self-interested. Thatunderstanding begins partially with Niccolò Machiavelli, whoadvised the prince to act from his own self-interest. A century later,Hobbes did not bother to advise acting from self-interest because hesupposed virtually everyone naturally does so. From that assumption, hewent on to give us the first modern political theory of the state, anexplanatory political theory that is not merely a handbook for theprince and that is not grounded in normative assumptions of religiouscommitment. To some extent, therefore, one could credit Hobbes with theinvention of social science and of explanatory, as opposed tohortatory, political theory.

Hobbes’s argument for the state is an argument from mutualadvantage. We all benefit if there is a powerful state in place toregulate behavior, thereby enabling us to invest efforts in producingthings to make our lives better and to enable us to exchange with eachother without fear that others will wreck our efforts. Some scholarssee this resolution as a matter of mutual cooperation in a grandprisoner’s dilemma. This is strategically or game theoretically wrongbecause putting a state in place is a matter of coordination on one oranother sovereign, not a matter of exchange among us or between us andthe sovereign. Once that state is in place, it might be true that Iwould rather free ride on the better behavior of my fellow citizens, whoare generally law-abiding. But I generally cannot succeed in doing so,because there is police power to coerce me if necessary.

What I cannot free ride on is the creation of a state. I want thestate, just as everyone who sees it as mutually advantageous wants it.Suppose that somehow, perhaps using the ring of Gyges to make meinvisible as Glaucon proposed, I could get away with theft or othercrimes. Even then, I would still want the state to have the power tocoerce people into order because if they are not orderly, they willproduce nothing for me to steal. If it is true, as Hobbes supposes,that having a state is mutually advantageous, it follows that we allwant it; and none of us can free ride on whether there is astate. Either there is one or there is not, and if there is one, then Iam potentially subject to its powers of legal coercion. On balance, Iwould want there to be an effective state for the protections it givesme against others despite its potential for coercing me into goodbehavior.

When we vote on a policy, as discussed above, we de facto change ourproblem from a collective-action prisoner’s dilemma into a simplecoordination problem by ruling out individual idiosyncrasies in ourchoices. We have only collective choice: provision for all or provisionfor none. Although the state is itself not the resolution of a giantprisoner’s dilemma or collective action, as is sometimes supposed, itcan be used to resolve prisoner’s dilemma interactions. Suppose you andI both want cleaner air but that each of us would free ride on theefforts of others to clean the air. State policy can block free riding,if necessary at metaphorical gunpoint. We both prefer the generaleffort to provide cleaner air and we both pay our share toward the costof providing it.

4. Explaining Collective Action

The facts that there is a lot of collective action even in manylarge-number contexts in which the individuals do not have richrelationships with each other and that, therefore, many people are notfree riding in relevant contexts suggest at least three possibilities.First, there are ways to affect the incentives of group members to makeit their interest to contribute. Second, motivations other thanself-interest may be in play. Third, the actors in the seeminglysuccessful collective actions fail to understand their own interests.Each of these possibilities is important and interesting, and thelatter two are philosophically interesting. Each is also supported byextensive empirical evidence.

In the first category are the by-product theory proposed byOlson and the possibility that political entrepreneurs, atleast partially acting in their own interest, can engineer provisions.In the by-product theory, I might contribute to my group’s effortbecause the group ties my contribution to provision of some privategood that I want, such as participation in the Sierra Club’s outdooractivities or, in the early days of unions, low-cost group-insurancebenefits not available in the market. Such private goods can commonlybe provided in the market, so that their usefulness may eventually beundercut. Indeed, firms that provide insurance benefits to theiremployees thereby undercut one of the appeals of union membership. Thegeneral decline of American unions in recent decades is partially theresult of their success in resolving problems for workers in ways thatdo not require continuing union effort.

When collective goods can be supplied by government or some otheragency, political entrepreneurs might organize the provision. Forexample, Senator Howard Metzenbaum worked to get legislation on behalfof the poor and of unions, although he was certainly not poor and wasnot himself a working member of a union. Yet he benefited from hisefforts in support of these groups if they voted to keep him in office.Because there is government, collective action of many kinds is farmore likely than we might expect from the dismal logic of collectiveaction.

Turn now to the assumption of self-interest. In generalizing fromthe motive of self-interest to the explanation and even justificationof actions and institutions, Hobbes wished to reduce political theoryto an analog of geometry or physics, so that it would be a deductivescience. All of the statements of the logic of collective action aboveare grounded in an assumption of the self-interested incentives of theactors. When the number of members of a group that would benefit fromcollective action is small enough, we might expect cooperation thatresults from extensive interaction, mutual monitoring, and evencommitments to each other that trump or block narrowly self-interestedactions. But when the group is very large, free riding is often clearlyin the interest of most and perhaps all members.

Against the assumption of purely self-interested behavior, we knowthat there are many active, more or less well funded groups that seekcollective results that serve interests other than those of their ownmembers. For a trivial example, none of the hundreds of people whohave been members of the American League to Abolish Capital Punishmentis likely to have had a personal stake in whether there is a deathpenalty (Schattschneider 1960, 26). In our time, thousands of peopleare evidently willing to die for their causes (and not simply to riskdying—we already do that when we merely drive to a restaurantfor dinner). Perhaps some of these people act from a belief that theywill receive an eternal reward for their actions, so that theiractions are consistent with their interests.

Finally turn to the possible role of misunderstanding in leadingpeople to act for collective provisions. Despite the fact that peopleregularly grasp the incentive to free ride on the efforts of others inmany contexts, it is also true that the logic of collective action ishard to grasp in the abstract. The cursory history above suggests justhow hard it was to come to a general understanding of the problem.Today, there are thousands of social scientists and philosophers who dounderstand it and maybe far more who still do not. But in the generalpopulation, few people grasp it. Those who teach these issues regularlydiscover that some students insist that the logic is wrong, that it is,for example, in the interest of workers to pay dues voluntarily tounions or that it is in one’s interest to vote. If the latter is true,then about half of voting-age Americans evidently act against their owninterests every quadrennial election year. It would be extremelydifficult to assess how large is the role of misunderstanding in thereasons for action in general because those who do not understand theissues cannot usefully be asked whether they do understand. But theevidence of misunderstanding and ignorance is extensive (Hardin2002).

5. Democracy

The logic of collective action has become one of the richest areasof research and theory in rational choice theory in the social sciencesand philosophy. Much of that literature focuses on the explanation ofvaried social actions and outcomes, including spontaneous actions,social norms, and large institutions. One of its main areas is effortsto explain behavior in elections. In general, voting seems clearly tobe a case of collective action for the mutual benefit of all those whosupport a particular candidate or whose interests would be furthered bythat candidate’s election. If voting entails costs to individualswhereas the benefit from voting is essentially a collective benefitonly very weakly dependent on any individual’s vote, individuals mayfind it in their interest not to vote (Downs 1957). When the number ofvoters on one side of an election is in the tens of millions, noindividual’s vote is likely to matter at all. Even though it is notnarrowly in their own individual interest to do so if there are anycosts to be borne in going to the polls to vote and in learning enoughabout various candidates to know which ones would further a voter’sinterests, millions of people vote. This is one of the most notoriousfailures of the rational choice literature. A standard response to thephenomenon of massive voting is to note how cheap the action is and howmuch public effort is expended in exhorting citizens to vote. But itseems likely that much of the voting we see is normativelymotivated.

Both the voting that does happen and the non-voting or free ridingthat accompanies it as well as the level of ignorance of voters callsimple normative theories or views of democracy into question.“The will of the people” is a notoriously hallowed phrasethat is vitiated by logical fallacy and that is generally meaninglessas a supposed characterization of democracy, in which decisions aremajoritarian and not unanimous (Kant [1796] 1970, 101; Maitland [1875]2000, 101–112). It might on rare occasion be true that the people arein virtually unanimous agreement on some important policy so that theyshare the same will on that issue. But generally, there is a diversityof views and even deep conflict over significant policies in modernpluralist democracies. In large societies, democracy is invariablyrepresentative democracy except on issues that are put to directpopular vote in referendums. Even this term,“representative,” is gutted by logical fallacy. Myrepresentative on some governmental body is apt to work on behalf of myinterests some of the time and against them some of the time. Eventhose for whom I vote often work against my interests; and if theyshould be said to represent me, they often do a very bad job of it.

Note that, as mentioned earlier, the election of a candidate is a goodwhose provision is a step function of the number of votes. If thereare n votes cast, then half of n − 1 votes spells defeatand half of n + 1 spells victory. If, as Mayor Daley did withthe Chicago votes in the US presidential election of 1960, I couldwithhold my vote until all others have been counted, my vote mightactually tip the result to victory for my candidate. In actual fact,the typical voter casts a vote in a state of ignorance about the finalcount. I might readily expect the margin to be very large or I mightexpect it to be very narrow. But I am unlikely to expect it to betied, so that my own vote would be decisive. Hence, although theactual provision is a step function, my vote or my free riding must bebased on some sense of the expected effect of my vote, and that mustgenerally be minuscule for any election in a large electorate. Withextremely high probability, my vote is likely to have no effect.

6. Free Riding and Morality

The fact that people do organize for collective purposes is oftentaken to imply the normative goodness of what they seek. If theby-product theory is correct, however, this conclusion is called intoquestion. For example, we might join a union merely to obtain insuranceat the inexpensive group rate even though we vote against all itsstrike proposals, would never join a picket line, and might even behostile to the idea of unions. Or we might go to a politicaldemonstration for varied reasons other than agreement with theostensible object of the demonstration; for example pro-war proponentsmight join in a peace march on a glorious day to hear performances byoutstanding singers in a large public park—something they mighthappily have paid to do.

It is also widely held that there are circumstances in which free riding on the provision of a collective good is morally wrong, because unfair. The two most prominent attempts to describe the conditions under which this kind of wrongness occurs are H.L.A. Hart’s principle of “mutuality of restrictions”:

when a number of persons conduct any joint enterprise according to rules and thus restrict their liberty, those who have submitted to these restrictions when required have a right to a similar submission from those who have benefited by their submission. (Hart 1955, 185)

and John Rawls’s “principle of fairness”:

a person is required to do his part as defined by the rules of an institution when two conditions are met: first, the institution is just (or fair), that is, it satisfies the two principles of justice; and second, one has voluntarily accepted the benefits of the arrangement or taken advantage of the opportunities it offers to further one’s interests. (Rawls [1971] 1999, 96)

Hart (1955, 185) calls his formulation a “bare schematic outline” of the obligation one owes to other cooperators; and subsequent discussion has focused on examining what is required in order to make this outline fully accurate. As it stands, Hart’s principle invites the kinds of objections emphasized by Robert Nozick (1974, 90–95): I am not morally required to pay for books that are thrown into my house with bills attached, or to take a day off work to entertain the neighbourhood over a public address system after my neighbours have taken it in turns to do so. Rawls’s formulation, which restricts the obligation to cases in which a benefit has been voluntarily accepted, avoids these objections. However, some writers argue that this is too tight a restriction (Arneson 1982; Cullity 1995; Trifan 2000): they maintain that when others are cooperating to produce a good that is compulsory, in the sense that once it is produced one cannot avoid receiving it (without excessive cost), one can still have an obligation of fairness to share the costs of producing it. If that is true, it keeps open the prospect (embraced by Hart but not Rawls) that political obligations can be grounded in an anti-free riding principle (Klosko 1992, 2005; Wolff 1995). However, the project of grounding political obligations in this way faces several significant obstacles. These include the objections that the operation of the state does not qualify as the kind of cooperative scheme to which a principle of fair contribution properly applies; that some citizens are sufficiently self-reliant that they do not receive a net benefit from the state; that grounding an obligation of fairness to contribute towards the cost of producing a collective good falls short of justifying the use of coercion to compel the contribution; and that an obligation to contribute to the production of a collective good does not apply when the question of which goods a group should be producing is itself contested.

One commonly claimed obligation of political participation is an obligation to vote. Support for this is sometimes attempted by appealing to a loose generalization argument that asks, “What if everybody failed to vote?” or, in the language here, “What ifeverybody chose to free ride on the voting of others?” Thepractical answer to that question, of course, is that everybody doesnot choose to free ride, only some do, and that it is exceedinglyunlikely that everyone will choose to do so. But if I think almost noone else will vote, I should probably conclude that it is thereforethen in my interest to vote (that day has yet to come). Perhaps thereis some number of citizens, k, such that, if fewer than k citizensvote, democracy will fail. If so, half of all citizens seems likely tobe a number significantly greater than k. Local elections in the USoften turn out far less than half the eligible citizens andpresidential elections turn out a bit more than half. One may questionjust what kind of democracy the US has, but it seems in somesignificant ways to work.

The generalization argument here is a variant of the fallacy ofcomposition and it is logically specious in its presumed implication.Yet many people assert such an argument in collective action contexts,and they may very well be motivated by the apparent moral authority ofthe argument. An alternative question here would be something like:“What if everybody failed to take into account the effect oftheir own vote on the election?” The answer is that roughly halfof Americans may well fail to take into account the effect of their ownvotes on elections, and they vote. The rest ride free.

Bibliography

- Andreoni, James, 1988, ‘Why Free Ride?: Strategies and Learning in Public Goods Experiments’, Journal of Public Economics, 37 (3): 291–304.

- Aristotle, 1998, Politics, trans. C.D.C. Reeve, Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Arneson, Richard J., 1982, ‘The Principle of Fairness and Free-Rider Problems’, Ethics, 92: 616–33.

- Axelrod, Robert, 1984, The Evolution of Cooperation, New York: Basic Books.

- Baumol, William J., 1952, Welfare Economics and the Theory ofthe State, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bentley, Arthur F., 1908, The Process of Government,Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bowles, Samuel, and Herbert Gintis, 2011, A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Binmore, Ken, 1998, Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 2: Just Playing, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Broad, C.D., 1916, ‘On the Function of False Hypotheses in Ethics’, International Journal of Ethics, 26: 377–97.

- Buchanan, J.M., 1968, The Demand and Supply of Public Goods, Chicago: Rand McNally.

- Cowen, Tyler (ed.), 1992, Public Goods and Market Failures: A Critical Examination, New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Cornes, Richard, and Todd Sandler, 1996, The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and Club Goods, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Cullity, Garrett, 1995, ‘Moral Free Riding’, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 24: 3–34.

- –––, 2008, ‘Public Goods and Fairness’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 86: 1–21.

- Dagger, Richard, 2000, ‘Membership, Fair Play, and Political Obligation’, Political Studies, 48: 104–17.

- de Jasay, Anthony, 1989, Social Contract, Free Ride: A Study of the Public Goods Problem, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Egas, Martijn, and Arno Riedl, 2008, ‘The Economics of Altruistic Punishment and the Maintenance of Cooperation’, Proceedings of the Royal Society: B, Biological Sciences, 275 (1637): 871–78.

- Ewing, A.C., 1953, ‘What Would Happen if Everyone Acted Like Me?’, Philosophy, 28: 16–29.

- Feiock, Richard C., and John Scholz (eds), 2010, Self-Organizing Federalism: Collaborative Mechanisms to Mitigate Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fischbacher, Urs, and Simon Gäächter, 2010, ‘Social Preferences, Beliefs, and the Dynamics of Free Riding in Public Goods Experiments’, The American Economic Review, 100 (1): 541–56.

- Frohlich, Norman, Joe A. Oppenheimer, and Oran R. Young, 1971, Political Leadership and Collective Goods, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gauthier, David, 1986, Morals by Agreement, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hampton, Jean, 1987, ‘Free-Rider Problems in the Production of Collective Goods’, Economics and Philosophy, 3: 245–73.

- Hardin, Russell, 1971, ‘Collective Action As an Agreeablen-Prisoners’ Dilemma’, Behavioral Science, 16 (September):472–481.

- –––, 1982a, Collective Action,Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- –––, 1982b, ‘Exchange Theory on StrategicBases’,Social Science Information 21 (2): 251–272.

- –––, 1997, ‘Economic Theories of theState’, Dennis C. Mueller (ed.), Perspectives on PublicChoice: A Handbook, New York: Cambridge University Press,pp. 21–34.

- –––, 2002, ‘The Street-Level Epistemologyof Democratic Participation’, Journal of PoliticalPhilosophy, 10 (2): 212–29.

- Hart, H.L.A., 1955, ‘Are There any Natural Rights?’, Philosophical Review, 64: 175–91.

- Hauser, Oliver P., David G. Rand, Alexander Peysakhovich, and Martin A. Nowak, 2014, ‘Cooperating with the Future’, Nature, 511: 220–23.

- Hobbes, Thomas, [1651] 1996, Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hume, David, [1739–40] 1978, A Treatise of Human Nature,L. A. Selby-Bigge and P. H. Nidditch (eds.) Oxford, Oxford UniversityPress, 2nd ed.

- Kameda, Tatsuya, Takafumi Tsukasaki, Reid Hastie, and Nathan Berg, 2011, ‘Democracy Under Uncertainty: The Wisdom of Crowds and the Free-Rider Problem in Group Decision Making’, Psychological Review, 118 (1): 76–96.

- Kant, Immanuel, [1796] 1970, ‘Perpetual Peace: APhilosophical Sketch’, Hans Reiss (ed.), Kant’s PoliticalWritings, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 93–115.

- Klosko, George, 1992, The Principle of Fairness and Political Obligation, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- –––, 2005, Political Obligations, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kollock, Peter, 1998, ‘Social Dilemmas: The Anatomy of Cooperation’, Annual Review of Sociology, 24: 183–214.

- Kurzban, Robert, Maxwell N. Burton-Chellew, and Stuart A. West, 2015, ‘The Evolution of Altruism in Humans’, Annual Review of Psychology, 66 (1): 575–99.

- Marwell, Gerald, and Ruth E. Ames, 1979, ‘Experiments on the Provision of Public Goods, I: Resources, Interest, Group Size, and the Free-rider Problem’, American Journal of Psychology, 84: 1335–1360.

- Maitland, Frederic William, [1875] 2000, A Historical Sketch ofLiberty and Equality, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

- McDermott, Daniel, 2004, ‘Fair-Play Obligations’, Political Studies, 52: 216–32.

- Mill, John Stuart, [1848] 1965, Principles of PoliticalEconomy, J. M. Robson (ed.), Collected Works of John StuartMill, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 7th edition, vols. 2and 3.

- Miller, David, 2004, ‘Justice, Democracy, and Public Goods’, in Dowding, Keith, Robert E. Goodin, and Carole Pateman (eds), Justice and Democracy: Essays for Brian Barry, Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press, pp. 127–49.

- Miller, Frank, and Rolf Sartorius, 1979, ‘Population Policy and Public Goods’, Philosophy and Public Affairs 8: 148–74.

- Nozick, Robert, 1974, Anarchy, the State, and Utopia, NewYork: Basic Books.

- Olson, Mancur, Jr., 1965, The Logic of Collective Action,Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ostrom, Elinor, 1990, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pareto, Vilfredo, 1935, The Mind and Society, Arthur Livingston (ed.), New York:Harcourt, Brace.

- Pecorino, Paul, 2015, ‘Olson’s Logic of Collective Action at Fifty’, Public Choice, 162 (3/4): 243–262.

- Pettit, Philip, 1986, ‘Free Riding and Foul Dealing’, The Journal of Philosophy, 83: 361–79.

- Plato, The Republic, trans. C.D.C. Reeve, Indianapolis:Hackett, 2004.

- Rawls, John, 1964, ‘Legal Obligation and the Duty of Fair Play’, in S. Hook (ed.), Law and Philosophy, New York: New York University Press, pp. 3–18.

- –––, [1971] 1999, A Theory of Justice, Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press.

- Samuelson, Paul A., 1954, ‘The Pure Theory of PublicExpenditure’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 36:387–389.

- Schattschneider, E. E., 1960, The Semi-Sovereign People,New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Schmidtz, David, 1991, The Limits of Government: An Essay on the Public Goods Argument, Boulder: Westview.

- Simmons, A. John, 1979a, ‘The Principle of Fair Play’, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 8: 307–37.

- –––, 1979b, Moral Principles and Political Obligations, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Smith, Adam, [1776] 1976, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causesof the Wealth of Nations, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sugden, Robert, 1993, ‘Thinking as a Team: Towards an Explanation of Nonselfish Behaviour’, Social Philosophy and Policy, 10: 69–89.

- Taylor, Michael, 1987, The Possibility of Cooperation, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Tomasello, Michael, 2016, A Natural History of Human Morality, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Trifan, Isabella, 2020, ‘What Makes Free Riding Wrongful? The Shared Preference View of Fair Play’, Journal of Political Philosophy, 28 (2): 158–80.

- Tuck, Richard, 1979, ‘Is There a Free-Rider Problem, and If So, What Is It?’, in Ross Harrison (ed.), Rational Action, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 147–56.

- –––, 2008, Free Riding Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Tuomela, Raimo, 1988, ‘Free Riding and the Prisoner’s Dilemma’, The Journal of Philosophy, 85: 421–27.

- –––, 1992, ‘On the Structural Aspects of Collective Action and Free-Riding’, Theory and Decision, 32: 165–202.

- Wolff, Jonathan, 1995, ‘Political Obligation, Fairness, and Independence’, Ratio, 8: 87–99.

Academic Tools

| How to cite this entry. |

| Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society. |

| Look up this entry topic at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). |

| Enhanced bibliography for this entryat PhilPapers, with links to its database. |

Other Internet Resources

[Please contact the author with suggestions.]

Related Entries

democracy | game theory | political obligation | prisoner’s dilemma | voting

Copyright © 2020 by

Russell Hardin

Garrett Cullity<garrett.cullity@anu.edu.au>

| Look up free ride, free-ride, or freeride in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Free ride, freeride, or freeriding may refer to:

Sports[edit]

- Free Riding, extreme horseback riding

Free Rider Jumps

Media[edit]

Film and television[edit]

- Free Ride (TV series), a Fox TV sitcom

- Free Ride (1986 film), a 1986 film

- A Free Ride, a 1915 American pornographic film and the earliest surviving American pornographic film

Music[edit]

- Free Ride (album), a 1977 album by Dizzy Gillespie

- Free Ride, a 1978 album by Marshall Hain

- Free Ride, a 2004 album by Carson Cole

Songs[edit]

- 'Free Ride' (song), a 1975 song by Dan Hartman for the Edgar Winter Group

- 'Free Ride', a song by Nick Drake on the album Pink Moon

- 'Free Ride', a song by Annabelle Chvostek on the album Bija

- 'Free Ride', a song by the Concretes on the album Nationalgeographic

- 'Free Ride', a song by Audio Adrenaline on the album Bloom

- 'Free Ride', a song by Mock Orange on the album First EP

- 'Free Ride', a song by Watashi Wa on the album Eager Seas

- 'Free Ride', a song by Black Label Society on the album Hangover Music Vol. VI

- 'Free Ride', a song by Embrace on the album All You Good Good People

Economics[edit]

- Fare evasion, euphemism 'free ride'

- Free riding (stock market), buying stocks without the money to cover the purchase

- Free-rider problem, the problem faced by non-excludable goods providers

Free Rider Codes

Other uses[edit]

- FreeRIDE, a Ruby integrated development environment in Watir

See also[edit]

Free Rider Examples